Моделируем Школу будущего

Исследование практик школьного образования Фабрики позитивных изменений

Доля частных школ в общем числе общеобразовательных организаций за последние два десятилетия выросла почти в 2,5 раза, свидетельствуют данные Института образования НИУ ВШЭ. Во многом это стало ответом на запрос рынка: для родителей становятся все более очевидными ограничения и недостатки образования по модели среднестатистической государственной школы, — и особенно, когда эта школа переместилась домой в период пандемии. Ответом на этот запрос стали и многочисленные новые образовательные подходы, которые активно предлагаются, как правило, частными школами — особенно теми, которые относят к числу «альтернативных». Зачастую, такие школы открываются родителями для своих детей — в ответ на ситуацию отсутствия на рынке удовлетворяющего их варианта. Все это рождает массу вопросов: что ждет Школу в будущем? Какой она должна быть? Может ли она быть отличной от той, которая есть сейчас? Эти и другие вопросы обсуждались в ходе исследования Фабрики позитивных изменений, посвященного разработке модели Школы будущего.

Дизайн исследования

Кабинетный обзор публикаций использовался для создания концептуального аппарата, при помощи которого было бы возможно описание школьного образования. В подготовительной части исследования рассмотрены источники информации о современных подходах к организации школьного образования в России и за рубежом. Они носили как теоретический характер и описывали концепты, которые позже использовались для формулирования гайда опросника, так и описательный характер с указанием важных кейсов образовательных моделей.

На основании выделенных концептов был составлен гайд экспертного опроса, целью которого было их содержательное наполнение с опорой на школьные кейсы. Всего в ходе исследования было опрошено 20 экспертов из разных сегментов исследуемого поля: представители педагогического сообщества, авторы собственных образовательных концепций, специалисты по управлению образованием. Задачей опроса было сопоставить разные точки зрения на перспективы развития образовательных практик в школе и составить схему, в соответствии с которой было бы возможно описывать школьный образовательный процесс, для его последующего моделирования в контексте Школы будущего.

В рамках кейс-стади были рассмотрены 27 частных учебных заведений среднего общего образования и государственных школ, образовательная модель которых отличается от модели обычной среднеобразовательной школы (СОШ). Такая выборка позволяет следовать стратегии наибольших различий в выборе кейсов — не претендуя на покрытие всей генеральной совокупности, предполагается рассматривать их различия, а не сходства.

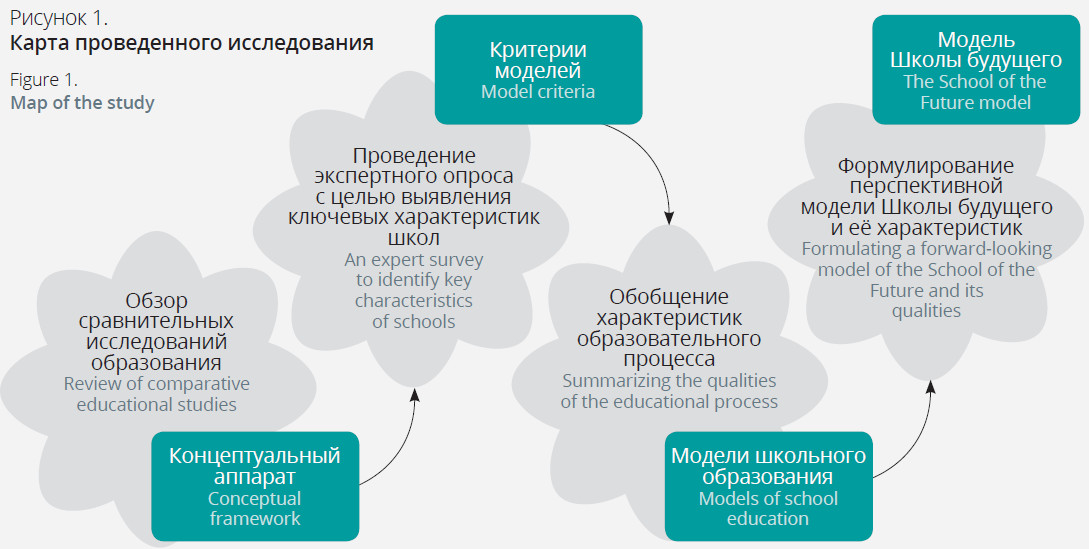

Далее выделенные критерии легли в основу описания ключевых моделей школьного образования. Модели имеют инструментальное значение — посредством них выделяются «точки роста», которые используются для формулирования перспективной модели Школы будущего и её характеристик.

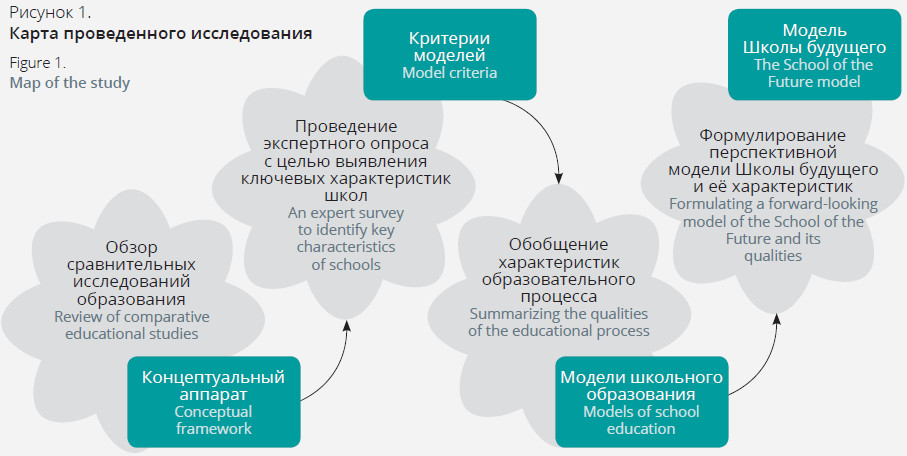

Таким образом, модель Школы будущего логически следует из концептов, полученных в результате обзора существующих исследований образования, посредством экспертных интервью и обобщения выделенных образовательных характеристик в критерии образовательных моделей. Описание этапов проведенного исследования и взаимосвязи между ними представлено на Рисунке 1.

Критерии выделения и анализа моделей школьного образования

Как было отмечено ранее, для проведения экспертного опроса на основании кабинетного исследования был составлен гайд. Основными концептами в опросе экспертов стали:

- ожидаемые образовательные результаты учеников Школы будущего (знания, умения и навыки, или иное);

- критерии для систематизации кейсов существующих учреждений среднего общего образования, указанных экспертами;

- образовательные модели на основании выделенных критериев.

Ожидаемые образовательные результаты (ключевые знания, умения и навыки)

Формулировка вопроса предлагала сфокусироваться на обсуждении не академических знаний (которые перечислить довольно сложно), но неких внепредметных навыков. Как сказал один из экспертов, «будущее остаётся неизведанным», в связи с чем ожидаемо, что главным навыком будущего эксперты чаще всего называли когнитивную гибкость. При этом этической основой для такой гибкости выступают уважение к другому и культура толерантности к иным ценностям. Важна терпимость не только к другому, но и к себе, к своим собственным ошибкам, которые становятся частью обучения.

Однако, помимо способностей к обучению, эксперты называли вполне конкретные умения, которым не принято учить в школе сейчас, но которые были бы крайне полезны человеку в жизни и в будущем. Одним из таких становится навык работы с контентом, который выступает и образовательным элементом, призванным отойти от лекционного формата, и элементом проектной деятельности, логике которой предстоит научиться члену общества будущего. При этом в хаотичном мире, где человеку предстоит быть гибким и адаптивным, важно учиться практикам заботы о себе — для чего важны знания о правильном питании, кулинарии и собственных ресурсах человека.

Ниже представлен список из ключевых названных экспертами компетенций, которыми должен обладать ученик Школы будущего. Каждая компетенция была названа минимум двумя экспертами.

Внепредметные компетенции

- Когнитивная гибкость: умение получать новые знания и решать новые, нетиповые задачи с использованием пройденного

- Интуитивность: возможность полагаться на «чутье»

- Уважение и понимание ценности себя, другого

- Сохранение и развитие мотивации к познанию

- Культура толерантности к ошибкам (своим и чужим) и неопределенности

Конкретные знания, умения и навыки

- Понимание базовых механизмов функционирования окружающего мира, исторических процессов

- Лингвистические навыки для изучения иностранных языков

- Навыки управления своими ресурсами и практики заботы о себе

- Основы кулинарии и нутрициологии

- Творческие навыки, навыки работы с контентом

Критерии моделей школьного образования

На основании проведенного опроса экспертов, были выделены три группы критериев: педагогические, инклюзивные и экономические.

Педагогические критерии отражают особенности учебного плана: индивидуализация, ориентация на академию или soft skills, дистанция между учеником и учителем, стиль общения с учениками и родителями. В широком смысле слова эта группа критериев относится к параметру индивидуализации образования.

Инклюзивность в широком смысле выделена в отдельную категорию критериев как характеристика доступности/комфортности образования для детей с особыми потребностями1, ценовая доступность для целевой аудитории, доступность в плане поступления (уровень «селективности»).

1Понятие «дети с особыми образовательными потребностями» охватывает всех учащихся, чьи образовательные потребности выходят за пределы некоторой, достаточно условно понимаемой средней нормы. Сюда входят дети с особенностями психофизического развития, одарённые дети, дети из социально уязвимых групп (например, воспитанники детских домов и т. д.). См. например: https://rosopeka.ru/articles/2895/86042/

Экономические признаки предлагались в основном специалистами по управлению образованием, которые рассматривали школьную модель не только со стороны образовательной части, но и как рыночный продукт. Потому данная сторона включает особенности рыночного предложения: насколько занят ребёнок в школе и может посещать в ней дополнительные занятия (секции, кружки и т.п.), окупается и масштабируется ли модель.

Ниже представлен список из ключевых названных экспертами критериев в оценке моделей школьного образования:

Педагогические критерии

- Возможность индивидуализации учебного плана: нет возможности, есть профилизация (наличие профильных классов, из которых можно выбирать свое направление), гибкий учебный план, разрабатываемый исходя из интересов и потребностей ученика (выбираются предметы, а не направления)

- Предметное содержание как следствие выбора образовательного результата: ориентация на академию или в сторону гибких навыков

- Стиль общения с учениками: коуч или лектор

- Стиль коммуникации с родителями: дашборды или просто оценки

- Возможность поступить в университет (как в России, так и за рубежом)2 после обучения: есть или нет

Инклюзивность

- Доступность для инклюзивных детей: доступно или нет

- Доступность в цене: финансовая доступность для целевой аудитории

- Наличие отбора: есть или нет

Экономические признаки

- Занятость ребёнка в школе: первая половина дня, опция дополнительных занятий, весь день

- Необходимость дополнительных услуг для окупаемости финансовой модели: есть или нет

- Возможность масштабирования: есть или нет

2Имеется в виду в первую очередь аттестация по результатам школьного образования — в формате ЕГЭ, позволяющего поступать в университеты в России, и/или IB либо других экзаменов, позволяющих поступать в университеты по всему миру

Обзор моделей школьного образования и их характеристики

Операционализация критериев образовательных моделей школ

В соответствии с ранее выделенными на основании сравнительных исследований образования и результатов экспертного опроса критериями оценки модели, решено обобщить их в виде следующего списка ниже. Соответствие моделей школьного образования каждому критерию предлагается оценивать по трехбалльной шкале:

Возможность индивидуализации учебного плана

♦ нет возможности

♦♦ есть профилизация (выбор направления)

♦♦♦ гибкий учебный план (выбор предметов и уровня их освоения)

Ориентация на «мягкие навыки»

♦ отсутствие ориентации на развитие «мягких навыков»

♦♦ ввод нескольких элементов программы для развития «мягких навыков»

♦♦♦ основной акцент в учебном плане сделан на развитии «мягких навыков»

Возможности дальнейшего получения университетского образования

♦ ученики готовятся к экзаменам самостоятельно, без выделения отдельной задачи по сдаче итоговых экзаменов

♦♦ учеников готовят к внутренним государственным экзаменам, позволяющим поступить в университеты в России (например, ЕГЭ)

♦♦♦ учеников готовят к сдаче международных экзаменов, позволяющих поступить в университеты за рубежом (например, IB)

Роль учителя как наставника

♦ учитель как лектор

♦♦ учитель как консультант по некоторым вопросам (например, в выборе образовательной траектории)

♦♦♦ учитель как тьютор, в том числе для развития внеакадемических навыков

Школа как центр развития сообщества

♦ школа не сотрудничает с местным сообществом, закрыта для него

♦♦ школа реализует отдельные проекты, вовлекая представителей местного сообщества

♦♦♦ школа активно вовлекает учеников в жизнь местного сообщества и вовлекает сообщество в школьную жизнь

Образовательная инклюзия

♦ доступность только для нейротипичных детей

♦♦ доступность для детей с особыми образовательными потребностями

♦♦♦ доступность и для «быстрых», и для «медленных» учеников — возможен максимальный учет индивидуальных особенностей ученика

Трекинг учебных достижений

♦ обычные оценки

♦♦ оценки с трекингом динамики результатов

♦♦♦ трекинг образовательных достижений и система обратной связи

Перечень образовательных моделей

В ходе проведения экспертных интервью опрошенные ссылались на набор моделей школ. На основании этого набора были отобраны опорные модели с учётом упоминаний экспертами, широты применения в практике и четкости рамок:

- Модель государственной СОШ — как точка отсчёта и сравнения.

- Государственная школа с профильными классами — на настоящий момент в России это самый распространённый девиант от массовой школы.

- Британская модель.

- Международный бакалавриат — как модифицированная международная версия британской модели.

- Альтернативные школы.

- Азиатская модель — много раз упоминалась экспертами, критерии применялись к опыту Сингапура.

- Финская модель.

Визуализация моделей

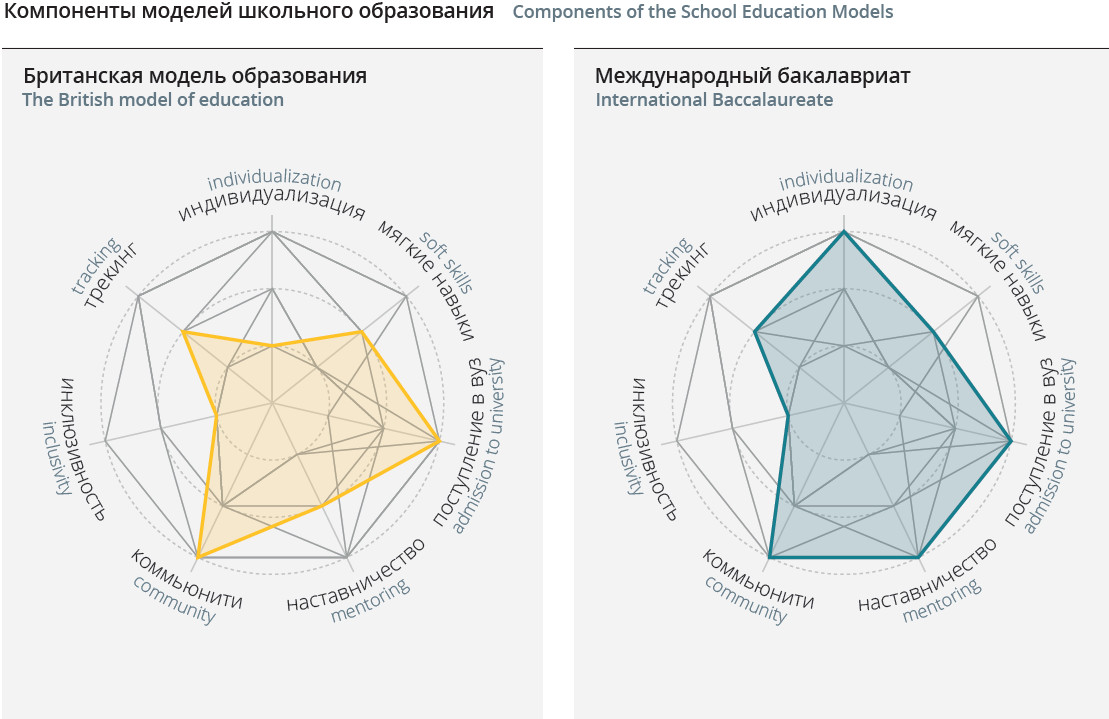

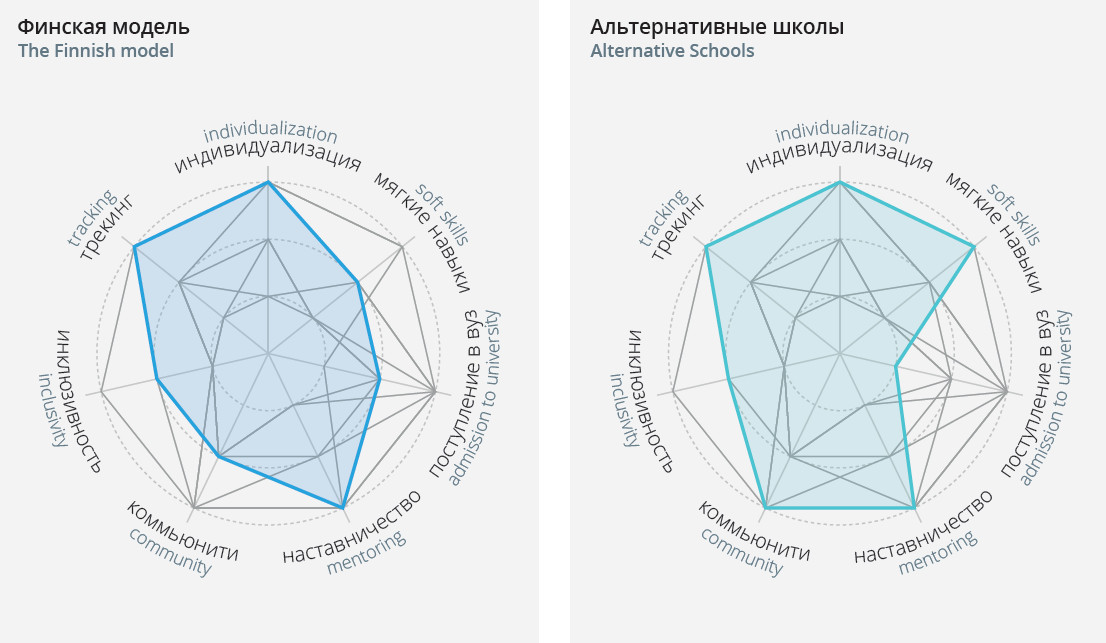

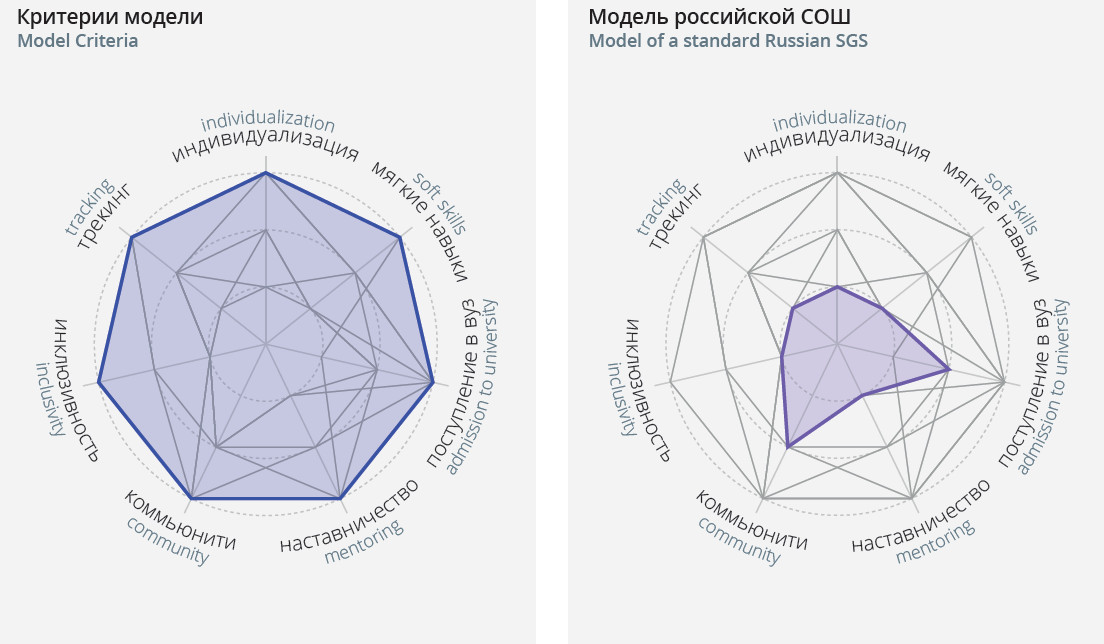

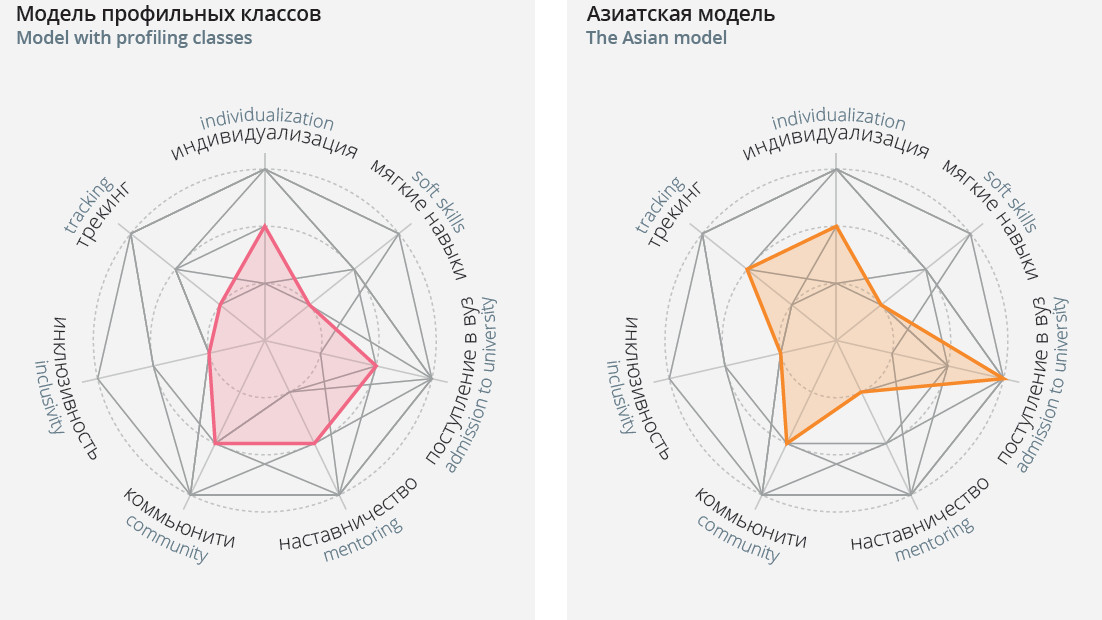

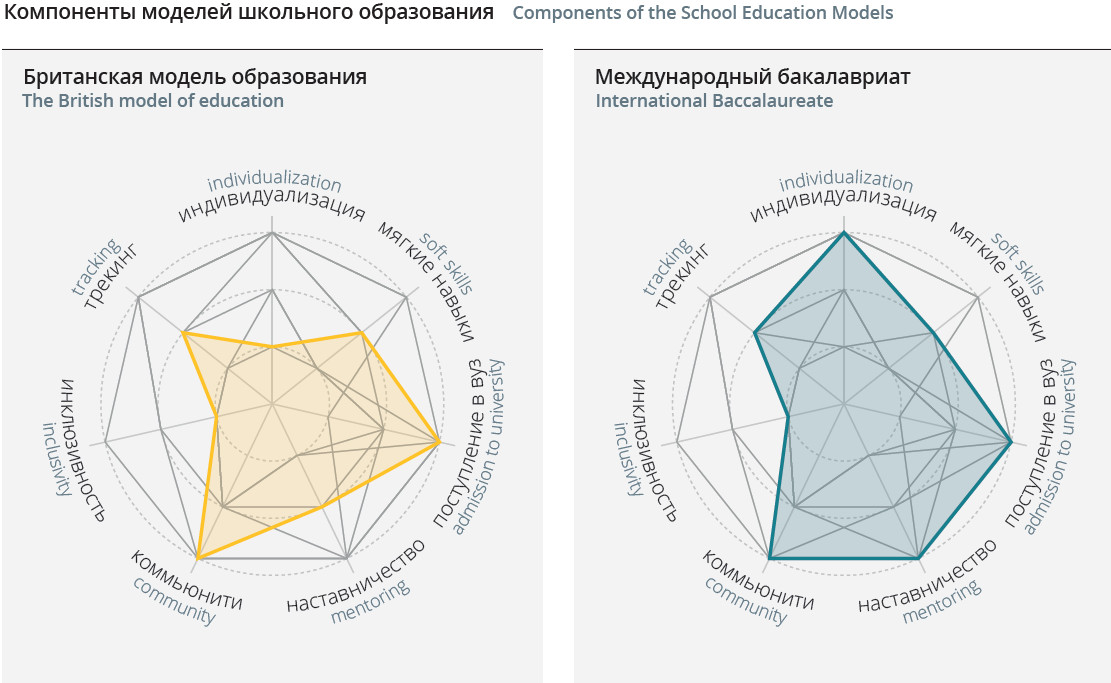

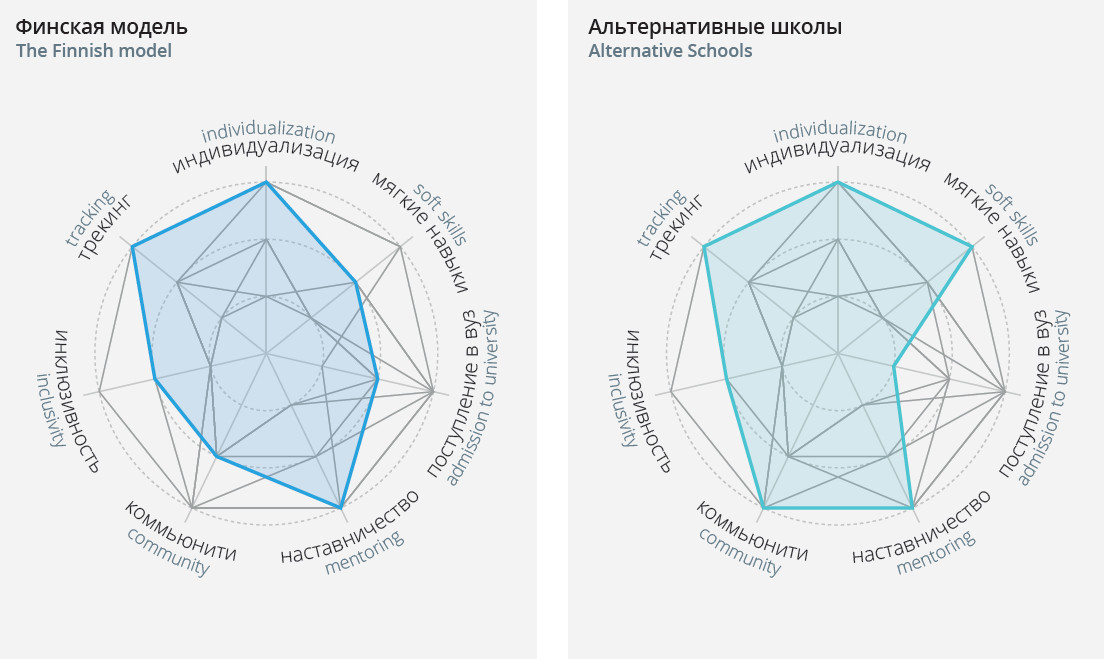

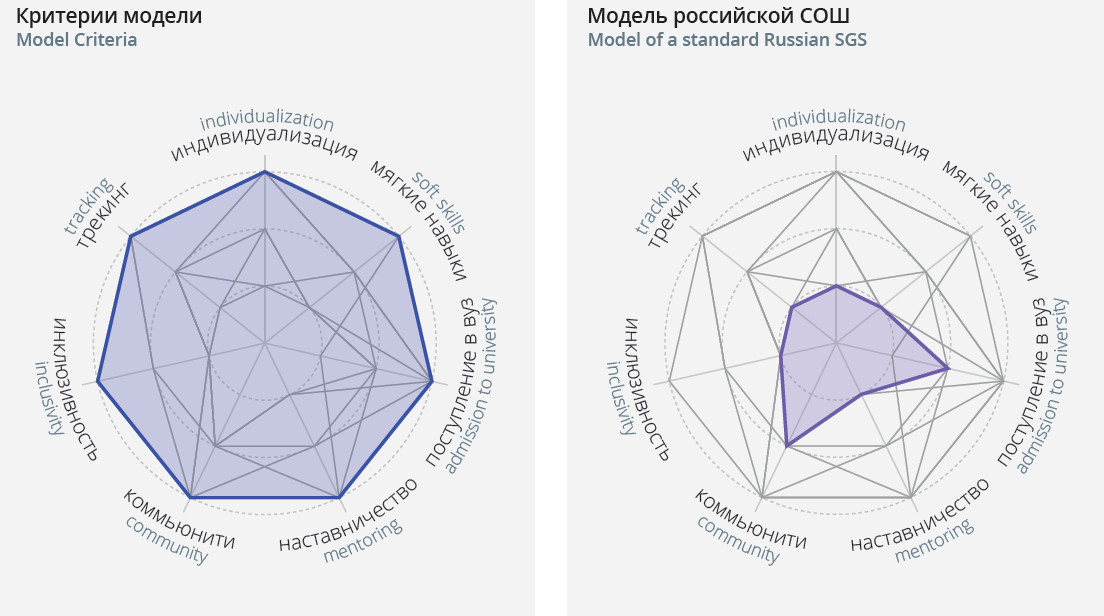

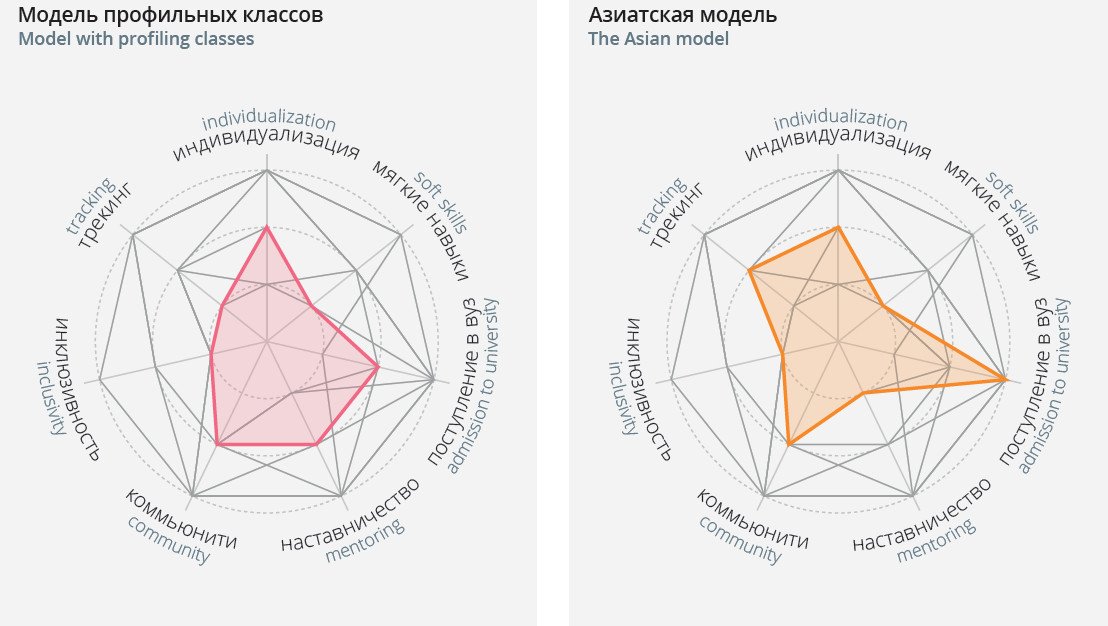

После изучения литературных источников, проведения экспертных интервью и анализа кейсов разных школ, каждой выявленной модели школьного образования был присвоен балл от 1 до 3 по каждому из 7 названных выше критериев. Ниже приведены лепестковые диаграммы для визуализации полного перечня моделей и присвоенных им баллов по каждому критерию.

Визуализации служат для демонстрации нескольких важных результатов.

Во-первых, можно заметить, что направленность на «мягкие навыки» и успешность поступления в вуз не встречаются одновременно в одних и тех же моделях, то есть предполагают определиться с приоритетными образовательными результатами.

Во-вторых, в широком смысле инклюзивность остаётся слабым местом всех моделей, даже тех, что подразумевают индивидуализацию.

Наконец, можно увидеть схожесть следующих пар моделей: российская и азиатская с радикальным вниманием к академическим успехам; финская модель и модель альтернативных школ, фокусирующихся на «мягких навыках»; британская модель и Международный бакалавриат как попытка академически оформить обучение «мягким навыкам».

Мы используем лепестковые диаграммы, чтобы подчеркнуть многомерность пространства образовательных моделей. Каждый критерий лежит в своей собственной концептуальной плоскости. Тем не менее, для операционализации моделей мы попробовали сократить количество измерений.

Построение единой схемы для классификации образовательных моделей затруднено тем, что они различаются по множеству признаков. Ярким примером, приведённым экспертом Института образования НИУ ВШЭ, здесь будут совершенно разные образовательные системы Финляндии и Шанхая: они обе относятся к верхам рейтингов по образовательным результатам, но достигают их через разные инструменты — гуманистический подход в Финляндии и «муштра» для массового образования Китая. Необходимо выстроить такую схему, которая могла бы показать содержательные различия между образовательными моделями.

В этом случае, возможными векторами могут быть «Централизация — Децентрализация» и «Индивидуализация — Массовость». Эти векторы будут использованы для классификации моделей на основании сформулированных критериев.

Вектор «Индивидуализация» образован следующими критериями:

- Возможность индивидуализации учебного плана

- Образовательная инклюзия

- Трекинг учебных достижений

Вектор «Децентрализация» включает следующие критерии:

- Роль учителя как наставника

- Школа как центр развития сообщества

Два из сформулированных выше семи критериев не вошли в указанные выше интегративные вектора. Это «Мягкие навыки» и «Поступление в вуз» — они не могут выступать компонентами выделенных векторов, но описывают отдельные, дополняющие их признаки.

Ниже приведена точечная диаграмма для визуализации полного перечня моделей и баллов, набранных моделями по осям «Индивидуализация» и «Децентрализация». Количество баллов по каждому вектору получено путем сложения баллов, набранных моделью по тем критериям, которые вошли в данный вектор (ось). То есть, например, для модели «Альтернативные школы» общий балл по оси «Индивидуализация» получен путем сложения баллов данной модели по трем критериям: возможность индивидуализации учебного плана, образовательная инклюзия и трекинг учебных достижений. 3 балла + 2 балла + 3 балла = 8 баллов, и так далее.

Диаграмма показывает, как модели соотносятся друг с другом в разрезе определённого набора критериев. Так, видно, что модель российской государственной СОШ отличается от азиатской в первую очередь по степени индивидуализации, с одинаковым уровнем централизации. На графике показано, что ранее выделенная пара моделей альтернативных и финских школ отличаются тоже только в одной плоскости, то есть отличаются по степени децентрализации. Заметно, что Международный бакалавриат, являясь модификацией британской модели образования, делает шаг в сторону альтернативных школ и финской модели в части децентрализации и индивидуализации.

Перспективные характеристики модели школы будущего

На основании выделенных критериев анализа моделей школьного образования, их содержательных характеристик, существующих образовательных моделей, нами выдвинуто несколько гипотез в отношении того, что должна включать в себя образовательная модель Школы будущего.

Проектно-ориентированная и проблемно-ориентированная технологии образования были отправными точками настоящего исследования и являются ключевыми современными педагогическими технологиями. Они шли лейтмотивом всех интервью и являются самой общей идеей: отойти от классно-урочной системы в сторону изучения какой-то темы, в рамках которой ученик получает междисциплинарное представление об исследовательской проблеме. Проектное обучение предполагает постановку цели, для выполнения которой учащиеся должны самостоятельно научиться новому. Из ранее не рассмотренных мотивов можно выделить два основных направления: 1) инклюзивность в широком смысле; 2) индивидуализация образовательной траектории.

Школа будущего — это инклюзивная школа, открытая для детей с самыми разными уровнями академических навыков. С одной стороны, есть дети с особыми образовательными потребностями, в поддержку которым приходят специалисты из ресурсного центра — нейропсихологи, логопеды, психологи. С другой стороны, есть дети, которые успевают учиться быстрее прочих. Чтобы создать благоприятную среду для детей разных скоростей обучения, можно создавать мобильные учебные группы для учеников с разным уровнем успеваемости по разным предметам, чтобы они получали соответствующий уровень учебного материала.

Индивидуализация образовательной траектории может быть достигнута не просто через профильные классы, но через формирование полностью индивидуального учебного плана, в разработке которого помогают тьюторы. Понять свой образовательный путь и сделать обучение более осознанными помогают системы качественной, не сводящиеся к количественной оценке, обратной связи. Важно снижение дистанции между учеником и учителем, расширение роли учителя как наставника.

В соответствии с особенностями метода создания частной школы, описанными экспертами, можно заключить, что особенностью образовательной модели будущего является то, чтобы предлагать не конкретные элементы программ учебных дисциплин, а предложить критерии разработки моделей под каждую конкретную школу.

Методической опорой для педагогической команды может стать «учёный совет» как проектная группа из людей, имеющих опыт запуска эффективных образовательных проектов. Для соблюдения и локализации модели, подготовки педагогических команд и тьюторов предлагается создать методический центр. Как автономный юнит и проектная команда, этот центр представляется как среда, в рамках которой будут создаваться педагогические коллективы школ. Сама педагогическая команда школы не может замыкаться на самой себе — для этого предусмотрены тренинги и обучение для учителей, в т. ч. от школьников. Такая конструкция, в первую очередь, ориентирована на формат массового внедрения инновационных школьных программ, в условиях, когда нет возможности привлечь «звездного директора», или собрать не менее «звездный» состав педагогов — так, как происходит сейчас при открытии новых частных школ.

Особенностью школы нового времени является то, что, помимо учебной нагрузки, ставится цель сформировать у ученика портфолио социальной деятельности, в чем ему будут помогать педагоги-наставники внутри школы и социально ответственные проекты по соседству со школой. Отдельную роль предлагается отвести вовлечению сообщества: через соседские центры и педагогический комитет школы создавать возможности для дополнительного образования учеников, организации стажировок и привлечение новых наставников и тьюторов.

Дискуссия о школе будущего

Вопрос о том, какой будет Школа будущего, остаётся открытым. Это можно продемонстрировать хотя бы тем фактом, что некоторые эксперты говорили о том, что малопродуктивно выделять какой-то конкретный набор навыков и компетенций ученика будущего. Говоря о модели Школы будущего, нужно понимать, что невозможно представить то будущее, в котором будут жить ученики этой школы. Поэтому Школа будущего не может существовать в отрыве от запросов учеников и их родителей, бизнеса и педагогического сообщества, общественного контекста и одной из главнейших ее характеристик становится гибкость и открытость изменениям, новому опыту. Школа становится не просто местом, где учат детей академическим навыкам, но центром сообщества, вовлекающим в свои события не только учеников, но и их родителей, жителей по соседству и из других районов города.

Навыки будущего — это по определению универсальные и гибкие навыки, которые могут пригодиться в разных контекстах. Школа будущего учит не откладывать жизнь на потом, но проживать в стенах школы жизнь в сообществе. Её ценности — это ответственность за свой персональный трек и за своё сообщество.

Глоссарий терминов для сравнения школьных моделей

Для описания кейсов и особенностей образовательного процесса требуются опорные категории из терминологического аппарата сравнительных исследований образования.

Проектно-ориентированное обучение (project-based learning) направлено на обучение решать практические задачи. Ученик вовлекается в материал через деятельность по разработке продукта и через командное взаимодействие (Казун, Пастухова, 2018).

Проблемно-ориентированное обучение (problem-based learning) представляет собой отказ от школьных предметов в сторону тематической группировки материала. Ученикам представляется проблема и теоретический материал для её решения. Модель подразумевает высокую автономию в изучении теоретического материала, мотивация изучать который закрепляется через актуальность проблемы (Ермакова, 2014).

Вопрошающее обучение (inquiry-based learning) фокусируется на центральном вопросе, на который ученику предлагается самостоятельно под кураторском учителя найти ответ. В этой модели акцент делается не на теоретическом материале, но на методах самостоятельного поиска ответа на вопрос (Pedaste, 2015).

Кейсы школ с перечисленными выше педагогическими технологиями позитивно отличаются от средней общеобразовательной школы не просто оценками учеников, но самой структурой образовательного процесса и образовательными результатами, которые трактуются шире, чем просто знания по предметам.

Технологии обучения как совокупность инструментов достижения образовательных результатов в организационном плане оформляются в виде организационных моделей. Организационные модели школ как способа организации учебных планов, функций и возможностей могут быть подразделены на типы, описанные ниже.

Малые учебные сообщества (small learning communities model) основываются на модели, при которой малая учебная группа преследует свой персонализированный учебный план и закреплена за набором преподавателей. Педагогический эффект усиливается за счет формирования чувства сообщества у учеников между собой и с учителями. Инструмент малых сообществ используется в школе «Апельсин» (Haynes, 2011).

Модель академии (academy model) рассматривает школу как предуниверситарий, видит учителя как лидера, а ученика — как индивида, подлежащего развитию. Модель предполагает ученическую самооценку, фокус на развитии академических навыков для поступления в университет. Также модель характеризуется смычкой с практическим сектором для профориентации учеников и продолжением профессионального образования учителей. Из иностранных кейсов на эту модель походит сингапурская школа Танглин Траст с её структурированной системой оценки и нацеленностью на поступление в университет (Hall, Clappe, 2016).

Интегрированное обучение (integrative learning) отходит от школьных предметов и связано с проблемно-ориентированным обучением: ученики проходят междисциплинарный подход в отношении какой-либо тематической области, вырабатывая навыки и знания сразу по нескольким дисциплинам. Условная «финская» модель образования подходит под это описание (Gürkan, 2021).

Предполагается, что каждая из описанных выше организационных моделей школ может быть сформулирована при помощи критериев и способна покрыть кейсы. Их преимуществом является то, что они описывают модели обучения на формальном уровне, нивелируя страновые и тематические различия.

Иван Смекалин

Иван Смекалин

Аналитик Фабрики позитивных изменений

Список литературы

1. Духанина, Л. Н., Мерцалова, Т. А., Беликов, А. А., Горбовский, Р. В., Заир-Бек, С. И. & Матюненко, Ю. А. (2019). Частные школы России: состояние, тенденции и перспективы развития. Аналитический доклад. Москва: НИУ ВШЭ.

2. Bray, M., Adamson, B., Mason M. (Ed.). (2014). Comparative education research: Approaches and methods. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978–3-319–05594–7

3. Казун, А., & Пастухова, Л. (2018). Практики применения проектного метода обучения: опыт разных стран. Образование и наука, 20(2), 32–59. https://doi.org/10.17853/1994–5639–2018–2-32–59

4. Ермакова, Е. А. (2014). Проблемно-ориентированное обучение: практика применения в системе высшего образования. В: Е. В. Веретённик & Н. Д. Стрекалова (Ред.). Case-study — образовательный и исследовательский опыт в междисциплинарном контексте: сборник научных статей по итогам междисциплинарного научного семинара кадрового резерва «Проблемы и перспективы использования метода case-study: междисциплинарный опыт» 30–31 мая 2013 года (c. 177–189). Санкт-Петербург: Отдел оперативной полиграфии НИУ ВШЭ.

5. Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., de Jong, T., van Riesen, S. A. N., Kamp, E. T., Manoli, C. C., Zacharia Z. C. & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review, 14, 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003

6. Haynes, J. (2011). The Impact of the Small Learning Community Model on the Students, Teachers, Administrators, and the Overall Culture of High Schools. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. Jones International University. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/openview/429f8cf09f5d5f5302c1e649e37338c5/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

7. Hall, T., & Clappe, A. (2016). North Dakota’s Experience with the Academy Model: a Successful Replication. Educational Considerations, 43(4). https://doi.org/10.4148/0146–9282.1009

8. Gürkan, B. (2021). Transdisciplinary integrated curriculum: An analysis of teacher experiences through a design model within the framework of IB-PYP. Participatory Educational Research, 8(1), 176–199. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.21.10.8.1

Modeling the School of the Future

A Study of Existing School Practices by the Positive Changes Factory

The share of private schools in the total number of educational institutions has increased almost 2.5-fold over the past two decades, according to a study by the Institute of Education of the National Research University Higher School of Economics. In many ways, this was a response to the market demand, with the parents becoming increasingly aware of the limitations and shortcomings of an education based on the average public school model — especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, when schooling moved home. Numerous new educational approaches that are actively offered, primarily by private schools, — especially those that classify as “alternative” schools — are another response to this demand. Such schools are often started by parents for their children in response to a situation where no satisfactory option exists in the market. All this raises multiple questions: What awaits the School in the future? What should it be like? Can it be different from what it is now? These and other questions were discussed in the Positive Changes Factory’s study on the School of the Future model.

Design of the study

A desk review of publications was conducted to develop a conceptual framework within which the school education could be described. In the preparatory part of the study, the authors consider sources of information about modern approaches to the organization of school education in Russia and abroad. These included both theoretical sources describing various concepts, which were used later to formulate the questionnaire guide, and narratives illustrating important case studies of educational models.

Based on the concepts highlighted, an expert questionnaire guide was compiled, with the purpose of providing meaningful content based on school case studies. A total of 20 experts from different segments of the field under study were interviewed. This included representatives of the teaching community, authors of their own educational concepts, specialists in education management. The objective of the survey was to compare different viewpoints on the prospective development of educational practices in the school and to produce a framework that would enable us to describe the school education process, so it can be modeled subsequently in the context of the School of the Future.

The case study examined 27 private general secondary education institutions and public schools with educational models different from that of a regular secondary general school (SGS). Having this sample enabled us to follow the strategy of greatest differences in case selection — without claiming to cover the entire general population, we are supposed to consider their differences rather than their similarities.

Further, the highlighted criteria formed the basis for describing the key models of school education. The models are instrumental in highlighting “growth points”, which are used to formulate a forward-looking model of the School of the Future and its characteristics. Thus, the School of the Future model logically follows from the concepts derived from reviewing the existing educational research through expert interviews and the synthesis of selected educational characteristics into the criteria of educational models. A description of the study stages and the relationship between them is presented in Figure 1.

Criteria for selecting and analyzing school education models

As noted earlier, a guide was developed for the expert survey based on a desk study. The main concepts in the expert survey were:

- expected educational outcomes of the School of the Future students (knowledge, abilities and skills, or others);

- criteria for classifying the cases of existing general secondary education institutions, as suggested by the experts;

- educational models based on the criteria identified.

Expected educational outcomes (key knowledge, abilities and skills)

The questions were worded so as to suggest focusing on discussing specific extracurricular skills, not the academic knowledge (which is quite difficult to list). As one expert said, “the future remains unexplored,” so it is quite expected that cognitive flexibility was the most frequently cited skill of the future. The ethical basis for this flexibility is respect for the others and a culture of tolerance for others’ values. Tolerance is important, not only for the other, but also for yourself, for your own mistakes, which become part of learning.

However, in addition to the learning abilities, the experts named some specific skills that are not commonly taught in school now, but which would be extremely useful to a person in life today and in the future. One of these is the content skill, which is both an educational element, designed to move away from the lecture format, and an element of project activity, the logic of which the member of the society of the future has to learn. In this chaotic world, where one has to be flexible and adaptive, it is important to learn the practices of self-care — for which it is important to have knowledge of good nutrition, cooking and one’s own resources.

Below is a list of key competencies named by the experts that a School of the Future student should possess. Each competency was named by at least two experts.

Extracurricular competencies

- Cognitive flexibility: the ability to acquire new knowledge and to solve new, non-typical problems using existing learnings

- Intuition: the ability to rely on a “gut feeling”

- Respect and understanding of the value of oneself and the others

- Maintaining and developing motivation for learning

- A culture of tolerance for mistakes (own and the others’) and uncertainty

Specific knowledge, skills and abilities

- Understanding the basic functioning mechanisms of the world around us, historical processes

- Linguistic skills for learning foreign languages

- Self-management skills and self-care practices

- Basics of Cooking and Nutritional Science

- Creative skills, content skills

Criteria for classifying school

education models

Based on the expert survey, three groups of criteria were identified: pedagogical, inclusive, and economic.

The pedagogical criteria reflect the curriculum features: personalization, focus on academic knowledge or soft skills, distance between student and teacher, communication style with students and parents. In a broad sense, this group of criteria refers to the personalization parameters of the education process.

Inclusivity, in the broad sense, is put in a separate category of criteria as a description of accessibility/comfort of education for children with special needs1, financial affordability for the target audience, and accessibility in terms of admission (level of “selectivity”).

1The concept of “children with special educational needs” encompasses all students whose educational needs go beyond some, rather conventionally understood, average norm. This includes children with special needs, gifted children, children from socially vulnerable groups (for example, children from orphanages, etc.). See for example: https://rosopeka.ru/ articles/2895/86042/

Economic criteria were proposed mainly by specialists in education management, who viewed the school model not only from the educational viewpoint, but also as a market product. Therefore, this aspect includes features of the market offer: how busy the child is at school and whether he/she can attend additional classes (sections, circles, etc.), and whether the model is financially sustainable and scalable.

Below is a list of the key criteria named by experts in evaluating school models:

Pedagogical criteria

- The possibility of curriculum personalization: not possible, profiling is available (profiling classes can be attended, to choose further direction of study), a fully flexible curriculum is developed that takes into account the interests and needs of the student (individual disciplines can be chosen, not overall directions)

- Discipline content dependent on the choice of educational outcome: focus on academic knowledge vs soft skills

- Style of communication with students: teacher as a coach vs lecturer

- Communication style with parents: dashboards vs simple grades

- Opportunity to enter a university (in Russia and abroad)2 after education: yes or no

2This primarily refers to certification based on the educational performance results — in the format of the USE, which allows entering universities in Russia, and/or IB or other examinations that allow entrance to universities around the world

Inclusivity

- Accessibility for inclusive children: accessible or not

- Affordability: affordability for the target audience

- Selection process: yes or no

Economic criteria

- The child’s occupation in school: first half of the day, optional classes, all-day studies

- The need for additional services to enable financial sustainability: yes or no

- Scalability: yes or no

Overview of school education models and their qualities

Putting the school education model criteria into operational perspective

In accordance with the model assessment criteria highlighted previously, based on the review of comparative educational studies and the results of the expert survey, it was decided to summarize them as per the list below. The alignment of school models with each criteria was evaluated on a 1 to 3 scale:

Ability to Personalize the Curriculum

♦ not possible

♦♦ profiling (choice of study direction) is available

♦♦♦ fully flexible curriculum (choice of subjects and their level)

Soft Skills Orientation

♦ lack of focus on the development of soft skills

♦♦ several elements are introduced in the curriculum for developing soft skills

♦♦♦ the curriculum is primarily focused on developing soft skills

Opportunities for Further University Education

♦ Students train for exams independently, passing the final exams is not set as a standalone objective

♦♦ Students are trained for domestic state exams, which allow them to enter universities in Russia (for example, the Unified State Exam)

♦♦♦ Students are trained to take international exams that allow them to enter universities abroad (e.g., International Baccalaureate)

The Teacher’s Role as a Mentor

♦ teacher as a lecturer

♦♦ the teacher as a consultant on certain issues (like the choice of educational path)

♦♦♦ teacher as a tutor, including in the development of extracurricular skills

School as a Community Development Center

♦ the school does not cooperate with the community, remains isolated

♦♦ the school implements individual projects involving community members

♦♦♦ The school actively engages students in the community life, and vice versa

Educational Inclusivity

♦ accessible only for neurotypical children

♦♦ accessible for children with special educational needs

♦♦♦ Accessible for both “fast” and “slow” students, with maximum consideration of the student’s individual performance level

Tracking Learning Achievements

♦ normal grades

♦♦ grades with performance tracking

♦♦♦ tracking of educational achievements with a feedback system

List of educational models

During the expert surveys, interviewees named

a set of school models. Based on this set, reference

models were selected, taking into account

the frequency of expert mentions, the breadth of

their practical application, and the clarity of the

framework:

- The standard Russian public secondary general school (SGS) — as a reference point and for comparison purposes.

- A public school with profiling classes is currently the most common modification of the mass school model in Russia.

- The British model.

- The International Baccalaureate is a modified international version of the British model.

- Alternative Schools.

- The Asian model — mentioned by the experts quite commonly, the criteria mainly applying to the Singapore experience.

- The Finnish model.

Model visualization

After reviewing the literature, conducting expert

interviews, and analyzing the cases of different

schools, each school education model identified

was assigned a score from 1 to 3 for each

of the 7 criteria named above. Below are spider

diagrams visualizing the full list of models and

assigned scores by each criteria.

Visualizations demonstrate several important

results.

First, we can notice that the focus on “soft

skills” and focus on University admission never

occur together in the same models; that is, they

are supposedly determining the priority educational

outcomes.

Second, in a broad sense, inclusivity remains

a weakness in all models, even those that imply

personalization.

Finally, we can see similarities in the following

model pairs: the Russian and Asian models,

which focus heavily on academic success;

the Finnish model and the model of alternative

schools focusing on “soft skills”; the British

model and the International Baccalaureate

as an attempt to frame soft-skills education

academically.

We use spider charts to emphasize the multidimensional

space of educational models. Each

criteria lies in its own conceptual plane. Nevertheless,

to put these models in the operational

perspective, we tried to reduce the number of

dimensions.

Building a single scheme to classify educational

models is difficult because they differ in many

ways. A striking example cited by an expert from

the Institute of Education of the National Research

University Higher School of Economics here would

be the very different educational systems of

Finland and Shanghai: while they both rank near the top in terms of educational outcomes, this is

achieved through different tools — the humanistic

approach in Finland and the “drilling” of the mass

education system in China. It is necessary to build

such a chart that could show the meaningful differences

between educational models.

In this case, two possible dimensions could

be “Centralization vs Decentralization” and “Personalization

vs Massiveness”. These vectors will

be used to classify models based on the criteria

formulated.

The “Personalization” vector consists of the following

criteria:

- Ability to personalize the curriculum

- Educational Inclusivity

- Tracking Learning Achievements

The “Decentralization” vector consists of the

following criteria:

- The teacher’s role as a mentor

- School as a center for community development

Two of the seven criteria formulated above

were omitted from the above integrative vectors.

These are “Soft Skills” and “Entering a University”,

which cannot act as components of the aforementioned

vectors but describe separate, complementary

attributes.

Below is a scatter chart visualizing the complete

list of models and their scores along the

“Personalization” and “Decentralization” axes. The

number of points for each vector is obtained by

adding the points scored by the model for the criteria included in the respective vector (axis). That is, for example, for the “Alternative Schools” model, the total score on the “Personalization” axis is obtained by adding this model’s scores in the following three criteria: curriculum personalization, educational inclusivity and tracking learning achievements. 3 points + 2 points + 3 points = 8 points, and so on.

The chart shows how the models relate to each other in terms of a certain set of criteria. Thus, we can see that the Russian state SGS model differs from the Asian model primarily in the degree of personalization, with the same centralization level. The chart also shows that the aforementioned model pair of alternative and Finnish schools also differs in only one plane: that is, the degree of decentralization. Remarkably,

the International Baccalaureate, being a modification of the British model of education, makes a step towards alternative schools and the Finnish model in terms of decentralization and personalization.

Prospective characteristics of the school of the future model

Based on the highlighted criteria in the analysis of school education models, the content and the qualities of the existing educational models, we put forward several hypotheses as to what the educational model of the School of the Future should include.

Project-oriented and problem-oriented technologies of education were the starting points of this study and are the key pedagogical technologies of today. They were the keynote of all the interviews and are the most general idea: to go away from classroom-lesson system toward the study of some topic in which the students get an interdisciplinary view of a specific problem researched. Project-based learning involves setting a goal for which students must independently learn new things. Of the motives left out so far, two main directions can be distinguished: 1) inclusivity in the broad sense; 2) personalization of the educational trajectory.

The School of the Future is an inclusive school open to children with a wide range of academic skills. On the one side of the scale, it includes children with special educational needs who are supported by specialists from the resource center — neuropsychologists, speech therapists, and psychologists. On the other side of the spectrum are children who manage to learn faster than others. To create a supportive environment for children of different learning speeds, mobile study groups can be created for students with different levels of achievement in different subjects so that everyone can receive the appropriate level of instructional material.

Personalization of the educational trajectory can be achieved not just through profiling classes, but through the development of a fully flexible, personalized curriculum, which the tutors help to develop. Qualitative, not quantitative, feedback systems help understand one’s educational path and make the learning more conscious. It is important to reduce the distance between the student and the teacher, expanding the teacher’s role as a mentor.

Following the peculiarities of the method for creating private schools, as described by the experts, we can conclude that the key feature of the educational model of the future is not to offer specific curriculum elements of academic disciplines, but to offer criteria for developing models for each specific school.

The methodological support for the teaching team can be provided by the “Academic Board”, a project group of people with experience in launching effective educational projects. To follow and localize the model, to train teaching teams and tutors, a methodological center can be set up. As an autonomous unit and a project team, this center is presented as an environment within which teaching teams will be created in schools. The teaching team at the school cannot be a thing in itself; training and education for teachers, including from students, are provided for this purpose. This design is focused primarily on the format of mass implementation of innovative school programs, in circumstances where there is no opportunity to attract a “celebrity principal” or assemble an equally “stellar” team of teachers, as is common with the opening of new private schools today.

A special feature of the school of the future is that, in addition to the teaching load, its goal is to form a student’s portfolio of social activities, in which he or she will be assisted by mentor teachers within the school and by socially responsible projects in the school’s community. Community engagement is expected to play an important role: the community centers and the school’s teaching committee will create additional education opportunities for the students, organize internships, and engage new mentors and tutors.

Discussion about the school of the future

The question of what the school of the future will be like remains open. This can be demonstrated at least by a few experts saying that it is unproductive to single out any particular set of skills and competencies for the student of the future. Speaking of the model school of the future, it is necessary to understand that it is impossible to imagine the future in which the students of this school will live, to begin with. Therefore, the school of the future cannot exist in isolation from the needs of the students and their parents, business and the teaching community, and the social context, and one of the most important qualities for the school of the future is flexibility and openness to change and innovation. The school is becoming more than just a place to teach children academic skills, but a community center that engages not only students, but also their parents and residents within the neighborhood and from other parts of the city.

Future skills are by definition versatile and flexible skills that can come handy in a variety of contexts. The School of the Future teaches us not to put life on hold, but to live a community life within the school walls. Its values are responsibility for your own personal track and for your community.

Glossary of terms for comparing school models

Describing the cases and features of the educational process requires using reference categories from the terminology of comparative educational studies.

Project-based learning focuses on learning to handle practical problems. The student is engaged in the material through product development activities and through team interaction (Kazun, Pastukhova, 2018).

Problem-based learning represents a shift away from school subjects toward a more topical grouping of material. Students are presented with a problem and theoretical material required for solving it. The model implies high autonomy in the study of theoretical material, the motivation to learn, which is reinforced through the relevance of the problem (Ermakova, 2014).

Inquiry-based learning focuses on a central question that the student is asked to answer independently, under the teacher’s supervision. In this model, the emphasis is made not on theoretical material, but on the methods of independently answering a question (Pedaste, 2015).

The cases of schools with the pedagogical technologies listed above differ positively from the average school — not just in student grades, but in the very structure of the educational process and educational outcomes, which are interpreted more broadly than mere subject knowledge.

Educational technologies, as a set of tools to achieve educational outcomes in organizational terms, are formalized in the form of organizational models. Organizational models of schools as a way of organizing curricula, functions, and opportunities can be categorized into the types described below.

Small learning communities are based on a model in which a small learning group pursues its own personalized curriculum and is assigned to a set of teachers. The pedagogical effect is enhanced by building a sense of community among the students and between students and teachers. The small communities tool is used at the Orange School (Haynes, 2011).

The academy model sees the school as a pre-university institution, where the teacher is a leader and the student is an individual to be developed. The model involves student self-assessment and a focus on developing academic skills for university admission. The model is also characterized by its linkage with the practical sector to provide career guidance for students and continuing professional education for teachers. The Tanglin Trust School of Singapore, with its structured grading system and focus on university admissions, resembles this model in foreign practice (Hall, Clappe, 2016).

Integrated learning moves away from school subjects and is associated with problem-based learning: students take an interdisciplinary approach to a subject area, developing skills and knowledge in several disciplines at once. The so-called “Finnish” model of education fits this description (Gürkan, 2021).

It is assumed that each organizational models described above can be formulated with the help of specific criteria and can cover specific cases. The advantage of these organizational models is that they give a formal description of the educational models, leveling out country and topical differences.

Educational Inclusivity

Educational Inclusivity

Accessible only for neurotypical children

References

1. Dukhanina, L.N., Mertsalova, T.A., Belikov A.A., Gorbovsky, R.V., Zair-Bek, S.I., Matyunenko, Yu.A. (2019). Private Schools in Russia: Current State, Trends, and Development Prospects. Analytical Report. Moscow: NRU HSE (In Russian).

2. Bray, M., Adamson, B., Mason M. (Ed.). (2014). Comparative education research: Approaches and methods. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05594-7

3. Kazun, A., & Pastukhova, L. (2018). The practices of project-based learning technique application: experience of different countries. Education and science, 20(2), 32–59. (In Russian). https://doi.org/10.17853/1994-5639-2018-2-32-59

4. Ermakova, E. A. (2014). Problem-based learning: practice of application in the higher education system. In: E. V. Veretennik & N. D. Strekalova (Eds.). Case study – educational and research experience in an interdisciplinary context: a collection of scientific articles on the results of interdisciplinary talent pool scientific seminar “Problems and Prospects of Using the Case Study Method: Interdisciplinary Experience” on May 30-31, 2013. (pp. 177–189). Saint Petersburg: Department of Operational Printing NRU HSE. (In Russian).

5. Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., de Jong, T., van Riesen, S. A. N., Kamp, E. T., Manoli, C. C., Zacharia Z. C. & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review, 14, 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003

6. Haynes, J. (2011). The Impact of the Small Learning Community Model on the Students, Teachers, Administrators, and the Overall Culture of High Schools. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. Jones International University. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/openview/429f8cf09f5d5f5302c1e649e37338c5/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

7. Hall, T., & Clappe, A. (2016). North Dakota’s Experience with the Academy Model: A Successful Replication. Educational Considerations, 43(4). https://doi.org/10.4148/0146-9282.1009

8. Gürkan, B. (2021). Transdisciplinary integrated curriculum: An analysis of teacher experiences through a design model within the framework of IB-PYP. Participatory Educational Research, 8(1), 176–199. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.21.10.8.1

DOI 10.55140/2782-5817-2022-2-S1-73-87

Хочешь стать одним из более 100 000 пользователей, кто регулярно использует kiozk для получения новых знаний?

Не упусти главного с нашим telegram-каналом: https://kiozk.ru/s/voyrl